Do you recognize this moment? You’re staring at your cash flow and revenue tracker and you can’t figure out what’s going on. Despite your agency having a really good month last month, hundreds of thousands in revenue, maybe more, your net profit was almost nothing. Where the fuck is our margin, you ask.

You are seeing plenty of other symptoms as well — your agency, a much happier place once upon a time, has grown, and at the same time strangely grown worse. It is a constant struggle to get work out the door, but it’s not a staffing problem; you have plenty of people to deliver the work you’ve sold. Maybe it’s efficiency, because it feels like work isn’t getting finished quickly enough, and yet everyone says they are busy. You ask managers what they think is going on and everyone has a different answer. You seem to be constantly “fixing” things, yet your organization still struggles. Can this be really that hard to fix?

It is.

Our team has worked with over 200 agencies to address exactly these questions, and the good news is that you’re not alone; almost every agency suffers from most if not all of these challenges. The challenges are solvable, though doing so requires a concentrated effort and technique. The problem is systemic, deeply rooted the many different stages of the agency’s sales and delivery model. At times, people call it scope creep, which is not quite accurate, or project overage, or a below-target effective billing rate, but we use the term rework, because its net effect is one of requiring work that should have been done right the first time — and for whatever reason was not — to be done again, often late and unexpectedly. Most rework arrives as an unwelcome guest, late to the meal and somewhat demanding.

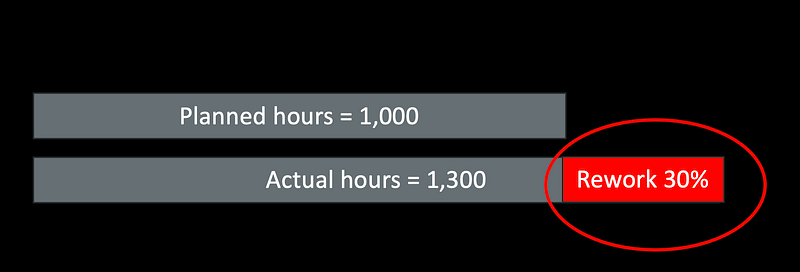

Calculate your rework using hours, the difference between the hours you thought (or hoped) you would need (as-sold), compared to the hours you actually used (as-delivered.) If a project was sold at 1,000 hours and delivered at 1,300 hours, then that’s a 30% rework rate. And those 300 hours are both lost revenue (because you can’t bill for them otherwise) and lost margin (because they increased your cost of the project, driving your effective rate down.

Most agencies have a rework rate somewhere between 20–40%, depending upon their work types. Because the origins of rework myriad, complex, and misunderstood, most agency leaders believe that they can simply grow their way out of it; that growth (scaling of the business) will deliver the needed relief. This almost always fails, because it is based on a flawed understanding of what type of organization an agency really is.

As I describe in my book, UNMANAGED, agencies are not scale-driven organizations, but rather they what are known as ad hoc project organizations, the type of organization that is optimal for delivering creative, innovative and unique project work. Size is the enemy of ad hoc organizations, and as we’ve noted in our decade-plus of industry work, once your agency passes 20–30 people in size, growth slowly degrades the operational model, an effect amplified by an increasingly multi-client, multi-manager, multi-project and multi-allocated complexity.

It is very worth fixing.

Rework is quite costly. Here’s an example.

A forty-person agency typically has annual services/project revenue around $5–7 million, maybe more. Drop the 25% rework rate down to 5% and recover 20% of those lost hours. It is easily a 7-figure number even in a small agency…if not in the first year, certainly by the second year. Larger agencies…well, it’s a no brainer. If you were able to claim even just half of that money and time back, then that’s still a pretty nice number. And you would get it back every day, and every year.

Nothing else affects margin so profoundly. Twenty-five percent is a big number! Strangely, many agencies seem to treat it as an immutable part of business. I had one COO scoff, “25% is not all that that bad for us”, while also admitting that the numbers I suggested were true. When did he decide to stop caring about all that margin?

Earlier this year, I was speaking with a somewhat grumpy small agency CEO (one of his operations leads had coerced him to take a call with me, and he assumed I was wasting his time.) He was complaining that getting more sales (growing through scale) didn’t seem to help. Despite some recent wins, his teams weren’t generating enough margin to hire more people, and so he risked burning out his teams.

I asked him what his rework rate was, and he replied, “What’s that?” I explained it, and he said, “Well, it sounds like we should be tracking that.” Yes, I think so. When I explained where it comes from and why, he said, “That sounds like something we should fix.”

Will he? Many don’t because they have “other initiatives” they are focusing on. Every agency has those initiatives, but none of those initiatives move the needle on margin like fixing your rework rate. Agencies are filled with managers — aren’t they supposed to be fixing this? Or even preventing it? No single manager can fix it because it is a broad and systemic problem, and most of them, inadvertently, are part of the problem. Rework is born and nurtured in what we call the broken scope-cycle that spans the whole lifecycle of client engagement.

A failed chain of custody

The broken scope-cycle is a chain of scope management mishaps that create a self-reinforcing loop. (Note: when I refer to “scope” I mean everything that you should know about the project, the client, its intended results, etc. “Scope” is not just the tasks that people are being told to do.)

The data we have collected from our key diagnostic workshops (the 18-point Lifecycle Diagnostic, and the Productivity Diagnostic), performed with over 80 agencies, suggest there are over a dozen key moments in the scope-cycle in which the quality and understanding of scope is in near-constant decline. Here are some of the key ones:

- You lost me at “Hello.” Agencies make a lot of promises when they’re pitching a new client or new piece of work. Almost universally, the agency itself knows they have very poor follow-through on those early conversations. Broken promises include how innovative they will be, how collaborative they will be, how deeply the teams will understand the client’s business, and how their work will create real business results.

- The absent and incomplete “Why.” In the rush to get going, often the tough questions are not asked of the client. Sometimes it is lack of skill in doing so, other times it is because one person expects that someone else, like a strategy person, will do it. But more often it is a “Three wise monkeys” problem: asking questions is curtailed by the very real fear that difficult questions may uncover complexities or uncertainties that blow up the sale, slow the project, or cause its scope to balloon. When we teach an agency our version of the “Why” technique using a new, real-life project, an agency will find 15 or more significant gaps in its understanding of the client context and the why behind the work, even after a signed contract.

- The ignorant handoff. When the work finally transitions from the sales or account people, much is still not known, and worse yet, the way the information is handed-off to the actual team is frighteningly ineffective, whether a briefing, a brief, a big PowerPoint deck, or even a specification. When we fix this through our trainings, you’ll hear account people say, “Wow, I wouldn’t have told them half of this.”

- The blindly optimistic and incomplete scope. Because so many details and potential risks have been (essentially) ignored, an agency has only an optimistic yet hazy idea of what the real work is. While much of what they have spoken about is fairly correct, the most important scope is the scope that they haven’t spoken about. Unexplored scope is a ticking time bomb of rework, guaranteed to go off at the worst possible moment. When we analyze this, sales scope versus the more-correct delivery scope, typically 30% of scope is hidden, unexplored, ticking away.

The 30% should be terrifying to you, but it is just an average, and not that bad compared to the extremes, both of which can create even larger problems. Sometimes unexplored scope is near 0%, this is a scope that is simple and well-understood, and rework, as a result, is minimal. But the fact that this happens with some regularity can be very misleading to agency management, creating a belief that the agency’s “system” works. And then, when things go wrong on other projects, managers conclude that it was not the system (because it has been proven to work), but some specific cause, some person, some client, some mistake. An agency is always fortunate to get some simple and well-understood projects, but it often misleads them into thinking that their system works, that they really know how to handle more-challenging scopes.

The other extreme — when scope is horribly unexplored — can be quite profound. One small agency client thought they had landed a $600k project, but when we showed them how uncover the unexplored scope, they found the project was three times larger than they had thought. Were it not for a supportive client, they might have had a true disaster on their hands, or gone out of business. This happens to the big guys as well. One of our largest clients ever, part of one of the largest holding companies, had agreed to a $2MM project, which upon the deeper examination, turned out to be $8MM. Both agency and client agreed to walk away from the project; nobody wants a disaster.

- The theft of the team’s scope. Most projects will go forward despite the incomplete and undiscovered scope. The “system” that worked so well for simple things now fails horribly, as only the scope that is known gets made into a plan. This does not fix things, and even tends to make them worse. This plan or schedule, ignorant of how much other work is really within this project, is inherently deceptive, missing 10–30% of its most important information. The plan is a lie, an inadvertent deception; because it suggests that everything is known when it is not. The teams are expected to deliver a project with missing scope following a schedule that for the same reasons lacks reality.

Managers are often unwittingly part of the problem, as the common practice of having managers “own” the scope, either individually, (as in a PM, who cannot ask the tough questions to find the hidden scope) or collectively (as a group of leads who will then hand pieces of incomplete scope down into their respective department silos.), means that nobody ever really sees the whole picture, certainly not the team.

- The fragmented, unaligned team. One of the other mistakes growing agencies make — believing themselves to be scale-based organizations — is fragmenting work into tasks, and workers into departments to “make things go better”. It doesn’t. The teams get spoon-fed only small pieces of scope, leaving them ignorant to the broader project and also their teammate’s work, which limits their ability deliver correct scope except through costly trial and error. These teams lack alignment: the ability to understand each other’s understanding. Alignment is the most important factor in successful teams’ execution in ad hoc project organizations.

- The stupid client. Clients are to blame for that scope creep, right? Nope. But they are the easiest to blame since they know the least. The fact that your agency did not fully-define scope, nor educate them to it, means that they are free to define (and re-define) it every time you try to deliver it. Agencies complain about client’s changing scope late in the project, but we’ve seen empirically that this is caused by the discovery of undiscovered scope late in the project. This is a direct result of the chain to failures to uncover and resolve missing scope, risks, and assumptions. The client is righteously stupid: if the agency did not ensure that all scope was understood and agreed to by the client, then the client has the right to change what wasn’t understood. In our Client Diagnostic workshop, the topic of “Clients don’t understand the project” is always in the top three types of agency-client challenges across their client base. Blame the client at your peril; it will keep you from ever fixing the real problem.

- The contagious Mt. Death March. And so, this project will be challenged to meet its schedule, quality, and margin goals. Your team is climbing Mt. Death March. But it gets worse when The Grim Reworker comes to visit. This wraith brings them the formerly undiscovered scope, now just a few, scant weeks before the delivery date, and they are going to need an extra 300 hours of work to get it done. Where do you find those people and hours? The only effective choice is to just keep the team together, but that means that the projects that they were scheduled to work on will now be delayed. This one bad project is making other, possibly good projects, go bad. It is the Grim Reworker’s plague of project contagion. Your other projects, including those which had simple and well-understood scope, will also suffer from staffing delays and other ills.

Boost margin by a million dollars or more: the Scope-Cycle makeover

One of our clients, Kevin Hourigan, CEO of Bay Shore Solutions, told me that before they worked with us, he would routinely write off a “big, six-figure number” at the end of each year. He went on to say that once they had mastered the scope-cycle fixes we taught them, it became a “four-figure number.” I didn’t ask whether it was a big or small four-figure number because, well, who cares? At that point, he had at least three years of those results.

Less rework means less labor cost per dollar of sales. That means you can either deliver more work without hiring (by growing sales), or you can deliver the same work with fewer people. You could also use the extra time to do better quality work. Or stop burning everyone out.

Many other problems in agencies are symptoms of the broken scope-cycle. In analyzing six years of data from our keystone workshop, the Agency Productivity Diagnostic, we’ve found that approximately 50% of all “delivery chaos” is caused by attempts to recover from failed parts of the scope-cycle. This includes symptoms that managers think can be solved directly (they can’t), such as: excessive meetings, excessive number of managers, delivery “misses,” lack of innovation or creativity, and low team morale.

Fixing the broken scope cycle creates real results. To quote one of our clients, LaneTerralever, whose case study is on our site: “…we’re up about 20% more dollars per hour of delivery. A lot of that is due to less re-work and better planning.”

Jack Skeels, CEO of AgencyAgile, is an award-winning author, entrepreneur, think-tank researcher, and leadership consultant. Jack’s work and company brings together decades of business research, cognitive and behavioral science, as well as practical techniques learned from working with over 200 organizations, into a set of simple lessons on how to more effectively manage, today’s complex, project-driven organizations. To learn more about how to make yours a better organization, visit AgencyAgile.com

Jack’s new book, UNMANAGED, a Gold Medal winner for “Independent Thought Leadership” at the 2024 Axiom Business Book awards, is available now on Amazon.