AI may accelerate some things, but that doesn't mean that the organization will go faster.

It’s common to ask why organizations don’t move faster. Speed is usually treated as something to be engineered: better tools, tighter processes, more urgency, fewer meetings. But this framing misses a more basic truth.

Organizations are not naturally slow.

In most cases, they are already working at full capacity. People are busy. Work is constantly in motion. What organizations struggle with is not effort, but friction—the forces that slow or reverse progress even when everyone is trying to move forward.

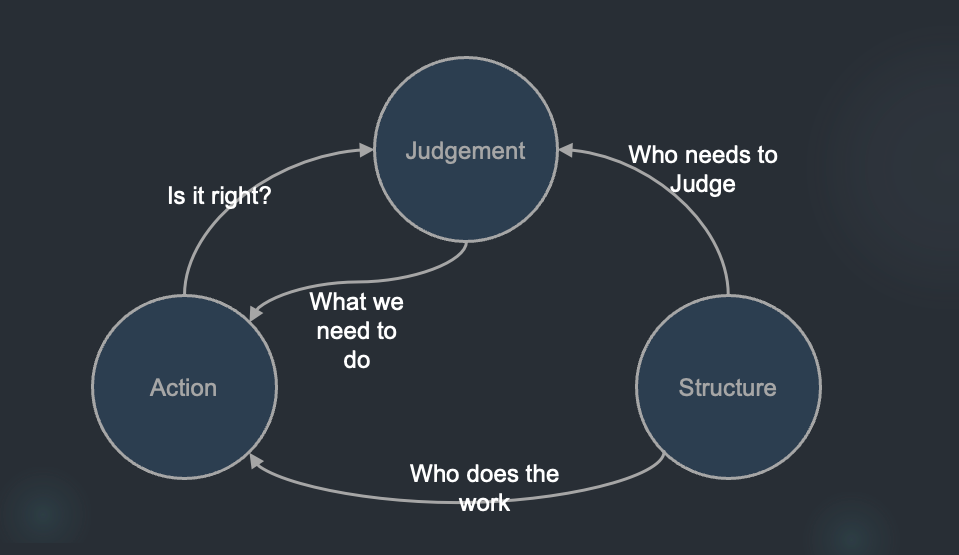

To understand where that friction comes from, it helps to separate three things that are often blurred together: action, judgment, and structure.

- Action is what an organization does: producing work, responding to clients, shipping deliverables, executing plans.

- Judgment is how an organization decides what actions make sense: interpreting context, aligning priorities, weighing tradeoffs, and determining what is “good enough” to proceed.

- Structure is how judgment and action are connected over time: who is allowed to decide, how understanding is shared, where authority sits, and how work moves from one person or group to another.

Every organization is constantly balancing these three. When they are well aligned, action flows naturally. When they are not, work advances in fits and starts—moving forward, then stalling, then looping back.

This is why organizations often feel slow even when activity is high. Action continues, but judgment struggles to keep up. Decisions feel close but take longer than expected. Alignment has to be re-earned. Work is revisited, revised, or undone. Teams stay busy, yet throughput remains stubbornly low.

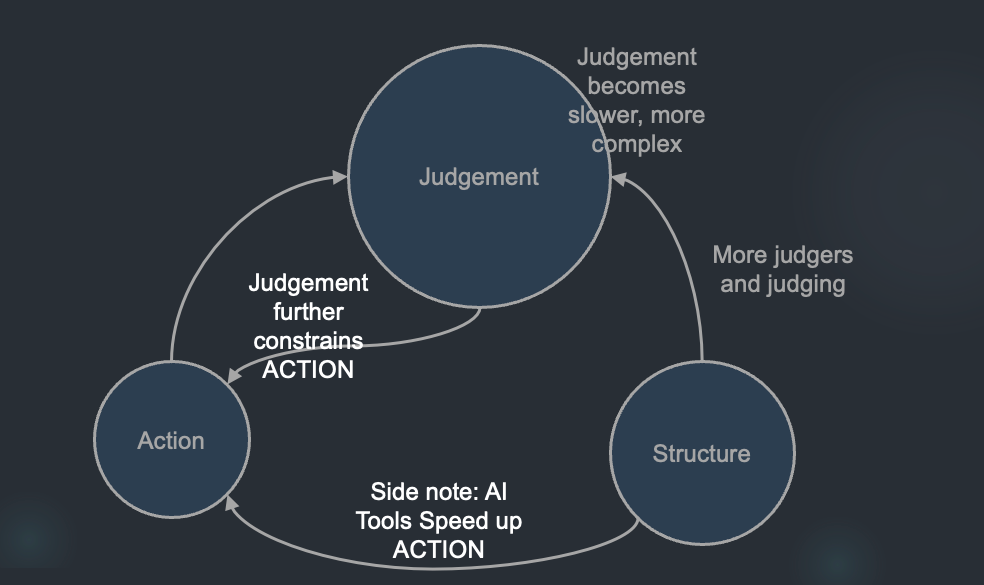

The rapid adoption of AI brings this imbalance into sharper focus. Much of the discussion around AI centers on tools, automation, and productivity gains. Far less attention is paid to what AI changes inside the organization itself. By dramatically accelerating action—generation, iteration, routing, execution—AI compresses the time available for judgment to operate. Action becomes cheap and abundant.

Action has always been thought of as the bottleneck, but what if it wasn't? What if judgment has really been the bottleneck, especially in high velocity organizations like agencies? If judgment has been the bottleneck, and action speeds up through AI, then judgment will become an even bigger bottleneck.

“Decision Latency,” is driven by the Complexity of the Judgement System

In the literature and in my work over the last few decades, complex, project-driven organizations, and likewise large-scale projects, are often diagnosed as struggling because of slow decisions. This diagnosis is understandable—decision latency is observable, measurable, and easy to point to. But it is also incomplete.

What appears as decision latency is more accurately a lagging indicator of judgment overload.

Judgment and decision are not the same thing. Decisions are discrete events—moments where commitment is made and action is authorized. Judgment, by contrast, is a continuous system of sense-making that includes understanding, interpretation, alignment, risk assessment, and legitimacy formation, to name a few. Decisions occur only when that system has cohered sufficiently to support action.

As organizational, stakeholder, and work complexity increase, the judgment system slows long before any formal decision is required. Context must be reconstructed, interpretations reconciled, assumptions revalidated, and alignment re-earned. Much of this work happens implicitly, without a named decision or an explicit blocker. Production velocity decreases or stalls not because a decision is missing, but because judgment is not yet safe enough (or well-enough understood) to act on.

Empirical studies that highlight decision latency—such as those from the Standish Group—are therefore identifying the symptom, not the cause. Decision latency correlates strongly with organizational drag because it reflects the point at which unresolved judgment is forced to surface. But the real cost is incurred earlier and more broadly: in slowed alignment, repeated re-understanding, defensive coordination, and hesitation without a formal decision in sight.

From a structural perspective, the problem is not slow decision-making. It is judgment that cannot cohere fast enough to keep pace with action under rising complexity. Organizations fail when their structures fragment judgment faster than it can be preserved, propagated, and reused.

The implication is profound: improving performance at scale is less about accelerating decisions and more about designing structures that protect judgment continuity—keeping understanding warm, alignment local, and interpretation close to the work. When judgment remains coherent, decisions arrive naturally and action proceeds without delay. When it decays, no amount of pressure or empowerment rhetoric can compensate.

Why Pods Worked: A Structural Explanation in Hindsight

Looking back, it’s clear that the primary impact of the "pods" technique was not speed in the narrow sense, nor even better execution. Pods worked because they repaired the judgment system in environments where complexity had made judgment fragile.

At the time, pods were often described in operational terms: fewer handoffs, tighter teams, reduced fragmentation and interruptive noise. These were all true, but they were surface effects. The deeper change was structural. Pods altered how judgment was formed, preserved, and translated into action.

First, pods dramatically reduced judgment decay. By keeping people assigned to a stable body of work, pods preserved context across time. Judgment did not need to be repeatedly reconstructed after interruptions or context switches. Understanding stayed warm. Alignment persisted. Decisions, when required, were grounded in a shared mental model rather than re-assembled from fragments.

Second, pods collapsed judgment distance. In many organizations, judgment travels through layers—account teams, project managers, review committees—before it authorizes action. Each handoff introduces delay and distortion. Pods shortened this path by placing judgment close to the work itself. The people best positioned to interpret signals and consequences were the same people empowered to act on them. This reduced latency without bypassing judgment.

Third, pods constrained the geometry of judgment. As organizations grow, judgment coordination can become combinatorial—managers judging managers judging managers. Pods created bounded spaces in which judgment could remain local and coherent. Cross-pod coordination still existed, but it became explicit and intentional rather than ambient and continuous. This prevented the geometric growth in judgment cost that so often drives managerial bloat.

Fourth, pods rebalanced the relationship between judgment and action. As action accelerated, pods ensured that judgment capacity per unit time did not collapse. By reducing unnecessary re-judgment and re-alignment, pods increased effective judgment bandwidth without adding layers of oversight. Action could move faster because judgment was already in place, not because it was bypassed.

Finally, pods changed the nature of managerial work. Managers were no longer required to constantly reconstitute judgment across fragmented efforts. Instead, they focused on maintaining the conditions under which judgment could remain coherent—clarifying goals, resolving true conflicts, and adjusting structure when complexity shifted. The result was not less management, but less compensatory management.

In hindsight, the productivity gains attributed to pods were gains in judgment efficiency: fewer judgments had to be made, those that remained were made earlier, and their results flowed directly into action. Speed emerged as a consequence.

What pods revealed—long before the language to describe it fully existed—is that in complex, project-driven organizations, performance is governed less by how fast people work and more by how well judgment survives structure and growth. Pods succeeded because they were not just teams; they were judgment-preserving structures.

The Structure–Judgment–Action Triangle Under Accelerated Activity

The deeper lesson beneath pods becomes clearer once we step back and look at the full relationship between structure, judgment, and action.

These three are not arranged in a linear chain. They form a mutually constraining triangle. Structure shapes how judgment is formed and how action is allowed. Judgment determines which actions are legitimate and when they can proceed. Action, over time, hardens into new structure. No side operates independently.

For a long time, this triangle remained in a kind of accidental balance. Action was slow and expensive. Judgment had time to form, align, and correct itself between actions. Structure absorbed inefficiencies by introducing latency—meetings, approvals, handoffs—that unintentionally protected the judgment system from overload.

That balance has now been disrupted.

AI dramatically increases activity velocity. Actions that once took hours or days can now be generated, repeated, and propagated in minutes or seconds. The organization’s ability to act has outpaced its ability to understand, align, and legitimize that action. Judgment velocity has not kept up.

This creates a structural inversion. Action no longer waits on judgment. Judgment is forced to chase action. Judgement becomes a bottleneck.

When that happens, organizations experience a familiar but poorly understood set of symptoms: decision latency spikes, alignment meetings proliferate, rework increases, and managerial layers thicken. These are not failures of decisiveness. They are attempts—often unconscious—to reintroduce friction into the action system so the judgment system can catch up.

Seen through the triangle, the problem is not that judgment has disappeared. It is that structure no longer regulates the coupling between judgment and action.

This is why accelerating execution without structural change produces paradoxical outcomes. Organizations feel simultaneously faster and more stuck. Activity increases, but throughput does not. Judgment becomes more expensive per unit of action, even as action itself becomes cheaper.

What our earlier pod implementations inadvertently demonstrated is that the solution is not to slow action or bypass judgment, but to redesign structure so judgment can remain continuous as activity accelerates. We have successfully implemented an advanced version of these techniques inside of a global agency where a large scale campaign saw reductions of span time by more than half, and labor cost reductions greater than 25%.

As increased AI tool utilization will cause activity velocity to rise, performance will be determined less by how quickly organizations can act and more by how well their structures maintain the integrity of judgment under speed. The winners will not be those that eliminate friction everywhere, but those that place friction intentionally, where judgment needs time, and remove it where judgment has already cohered.

In that sense, the problem AI introduces is like all major disruptive technologies in that its impact is fundamental and architectural. It forces organizations to confront whether their structures were ever designed to manage judgment at the pace their actions now permit.